Step 2: Pick a theory, model, and/or framework

Where to start? There are so many!

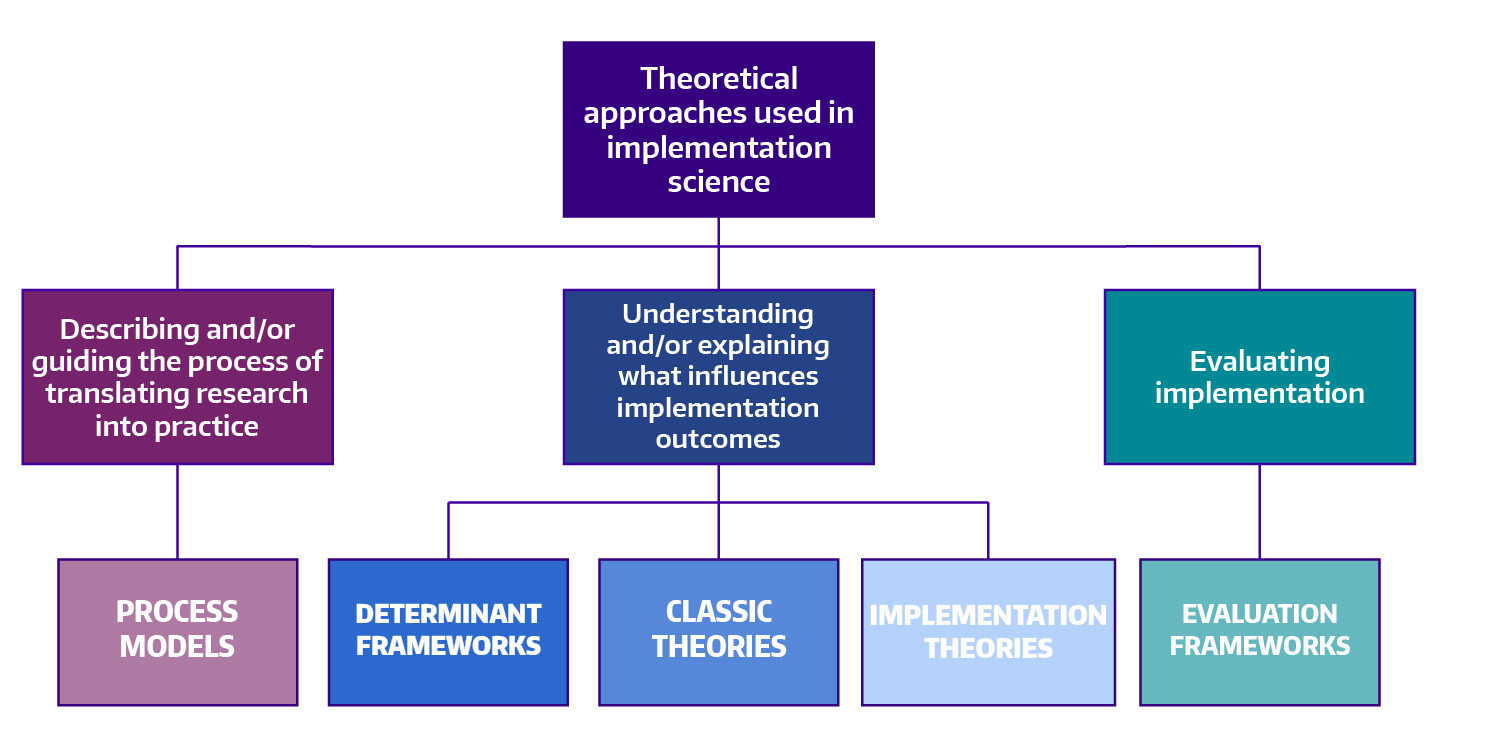

One of the cornerstones of implementation science is the use of theory. These theories, models, and frameworks (TMFs) provide a structured approach to understanding, guiding, and evaluating the complex process of translating research into practical applications, ultimately improving healthcare and other professional practices.

Theories, models, and frameworks serve several critical functions in implementation science. They help researchers and practitioners comprehend the multifaceted nature of implementation processes, including the factors that influence the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of interventions. TMFs offer structured pathways and strategies for planning and executing implementation efforts, ensuring that interventions are systematically and effectively integrated into practice. Additionally, they provide criteria and methods for assessing the success of implementation efforts, identifying barriers and facilitators, and informing continuous improvement. To learn more about the use of theory in implementation science, read Harnessing the power of theorising in implementation science (Kislov et al, 2019) and Theorizing is for everybody: Advancing the process of theorizing in implementation science (Meza et al, 2023)

There are dozens of TMFs used in implementation science, developed across a wide range of disciplines such as psychology, sociology, organizational theory, and public health. Some well-known examples include the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which identifies constructs across five domains that can influence implementation outcomes; the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) Framework, which emphasizes the importance of involving stakeholders at all levels and stages of the implementation process; and the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) Framework, which focuses on the interplay between evidence, context, and facilitation in successful implementation.

The vast number of available TMFs can make it challenging to determine which is the most appropriate to address or frame a research question. Two notable reviews provide schemas to organize and narrow the range of choices. Nilsen (2015) categorizes TMFs into five types: process models, determinants frameworks, classic theories, implementation theories, and evaluation frameworks. Tabak et al. (2013) organizes 61 dissemination and implementation models based on construct flexibility, focus on dissemination and/or implementation activities, and socio-ecological framework level.

✪ Making sense of implementation theories, models, and frameworks

(Nilsen, 2015)

Theoretical approaches enhance our understanding of why implementation succeeds or fails, so by considering both process models and determinant frameworks, researchers and practitioners can improve the implementation of evidence-based practices across various contexts.

Nilsen's schema sorts implementation science theories, models, and frameworks into five categories:

- Process models: These describe or guide the translation of research evidence into practice, outlining the steps involved in implementing evidence-based practices.

- Determinants frameworks: These focus on understanding and explaining the factors that influence implementation outcomes, highlighting barriers and enablers (but may lack specific practical guidance).

- Classic theories: These are established theories from various disciplines (e.g., psychology, sociology) that inform implementation.

- Implementation theories: These have been specifically designed to address implementation processes and outcomes.

- Evaluation frameworks: These assess the effectiveness of implementation efforts, helping evaluate whether the intended changes have been successfully implemented.

While there is some overlap between these theories, models, and frameworks, understanding their differences is essential for selecting relevant approaches in research and practice.

Adapted from: Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1-13.

Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research

(Tabak, Khoong, Chambers, & Brownson, 2013)

Rachel Tabak and colleagues organized 61 dissemination and implementation theories, models, and frameworks (TMFs) based on three variables to provide researchers with a better understanding of how these tools can be best used in dissemination and implementation (D&I) research.

These variables are:

- Construct flexibility: Some are broad and flexible, allowing for adaptation to different contexts, while others are more specific and operational

- Focus on Dissemination or Implementation Activities: These range from being dissemination-focused (emphasizing the spread of information) to implementation-focused (emphasizing the adoption and integration of interventions)

- Socioecologic Framework level: Addressing system, community, organization, or individual levels, with fewer models addressing policy activities

The authors argue that classification of a TMF based on these three variables will assist in selecting a TMF best suited to inform dissemination and implementation science study design and execution and answer the question being asked.

For more information, watch: 💻 Applying Models and Frameworks to D&I Research: An Overview & Analysis, with presenters Dr. Rachel Tabak and Dr. Ted Skolarus.

The IS Research Pathway

🎥 Videos from our friends

Dr. Charles Jonassaint, University of Pittsburgh Dissemination and Implementation Science Collaborative

Dr. Rachel Shelton, ScD, MPH & Dr. Nathalie Moise, MD, MS, FAHA, Columbia University

Dr. Meghan Lane-Fall, MD, MSHP, FCCM, Penn Implementation Science Center (PISCE)

✪ Using implementation science theories and frameworks in global health (BMJ Global Health, 2019)

✪ A scoping review of implementation science theories, models, and frameworks — an appraisal of purpose, characteristics, usability, applicability, and testability (Implementation Science, 2023)

✪ Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice (Implementation Science Communications, 2020)

Understanding implementation science from the standpoint of health organisation and management: an interdisciplinary exploration of selected theories, models and frameworks (Journal of Health Organization and Management, 2021)

💻 Toolkit Part 1: Implementation Science Methodologies and Frameworks (Fogarty International Center)

🎥 Implementation Science Theories, Frameworks, and Models (UAB CFAR Implementation Science Hub)

🎥 Theories and Frameworks in Implementation Science (Interdisciplinary Research Leaders)

A Selection of TMFs

While both ways of viewing this array of tools are useful, below we borrow from Nilsen’s schema to organize overviews of a selection of implementation science theories, models, and frameworks. In each overview, you will find links to additional resources.

Open Access articles will be marked with ✪

Please note some journals will require subscriptions to access a linked article.

Process Models

Used to describe or guide the process of translating research into practice

The need to adapt to local context is a consistent theme in the adoption of evidence-based practices, and Aarons and colleagues created the Dynamic Adaption Process to address this need. Finding that adaptation was often ad hoc rather than intentional and planned, the Dynamic Adaption Process helps identify core components and adaptable characteristics of an evidence-based practice and supports implementation with training. The result of the Dynamic Adaption Process is a data-informed, collaborative, and stakeholder-driven approach to maintaining intervention fidelity during evidence-based practice implementation, addressing real-world implications for public sector service systems and is relevant at national, state, and local levels. The framework development article, Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention, was published in 2012 in the open access journal, Implementation Science.

Examples of Use

- ✪ “Scaling-out” evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems (Implementation Science, 2017)

- ✪ Implementing measurement-based care in community mental health: a description of tailored and standardized methods (Implementation Science, 2018)

- ✪ “I Had to Somehow Still Be Flexible”: Exploring Adaptations During Implementation of Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Primary Care (Implementation Science, 2018)

- An Implementation Science Approach to Antibiotic Stewardship in Emergency Departments and Urgent Care Centers (Academic Emergency Medicine, 2020)

- ✪ Initial adaptation of the OnTrack coordinated specialty care model in Chile: An application of the Dynamic Adaptation Process (Frontiers in Health Services, 2022)

Recognizing that implementation science frameworks were largely developed using research from business and medical contexts, Aarons, Hurlburt, and Horwitz created the four-phase implementation model EPIS (Exploration, Adoption/Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment) in 2010 to address implementation in public service sector contexts. The EPIS framework offers a systematic approach to understanding and implementing evidence-based practices, considering context, and ensuring sustainability throughout the process. The framework development article, Advancing a Conceptual Model of Evidence-Based Practice Implementation in Public Service Sectors, is available open access (✪) from Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. You can also learn more by visiting EPISFramework.com.

In 2018 the authors refined the EPIS model into the cyclical EPIS Wheel, allowing for closer alignment with rapid-cycle testing. A model for rigorously applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework in the design and measurement of a large-scale collaborative multi-site study is available Open Access (✪) from Health & Justice.

Learn More

- ✪ Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework (Implementation Science, 2019)

- A Review of Studies on the System-Wide Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Veterans Health Administration (Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 2016)

- Advancing Implementation Research and Practice in Behavioral Health Systems (Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 2016)

- ✪ A model for rigorously applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework in the design and measurement of a large scale collaborative multi-site study (Health and Justice, 2018)

- Characterizing Shared and Unique Implementation Influences in Two Community Services Systems for Autism: Applying the EPIS Framework to Two Large-Scale Autism Intervention Community Effectiveness Trials (Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 2019)

- ✪ ✪ Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework (Implementation Science, 2019)

- ✪ The core functions and forms paradigm throughout EPIS: designing and implementing an evidence-based practice with function fidelity (Frontiers in Health Services, 2024)

- 💻 WEBINAR: Use of theory in implementation research: The EPIS framework: A phased and multilevel approach to implementation

In 2012 Meyers, Durlak, and Wandersman synthesized information from 25 implementation frameworks with a focus on identifying specific actions that improve the quality of implementation efforts. The result of this synthesis was the Quality Implementation Framework (QIF), published in the American Journal of Community Psychology. The QIF provides a roadmap for achieving successful implementation by breaking down the process into actionable steps across four phases of implementation:

- Exploration: In this phase, stakeholders explore and consider the need for implementing a specific intervention

- Installation: This phase involves planning and preparing for implementation

- Initial Implementation: The intervention is put into action during this phase

- Full Implementation: The focus shifts to sustaining the intervention over time

Examples of Use

- ✪ Practical Implementation Science: Developing and Piloting the Quality Implementation Tool (American Journal of Community Psychology, 2012)

- Survivorship Care Planning in a Comprehensive Cancer Center Using an Implementation Framework (The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, 2016)

- ✪ The Application of an Implementation Science Framework to Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs: Be a Champion! (Frontiers in Public Health, 2017)

- ✪ Developing and Evaluating a Lay Health Worker Delivered Implementation Intervention to Decrease Engagement Disparities in Behavioural Parent Training: A Mixed Methods Study Protocol (BMJ Open, 2019)

- Implementation Process and Quality of a Primary Health Care System Improvement Initiative in a Decentralized Context: A Retrospective Appraisal Using the Quality Implementation Framework (The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 2019)

Determinant Frameworks

Used to understand and/or explain what influences implementation outcomes

In 2005, the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN) published an Open Access (✪) monograph synthesizing transdisciplinary research on implementation evaluation. The resulting Active Implementation Frameworks (AIFs) include the following five elements: Usable Intervention Criteria, Stages of implementation, Implementation Drivers, Improvement Cycles, and Implementation Teams. A robust support and training website is maintained by NIRN, complete with activities and assessments to guide active implementation.

Learn More:

- Statewide Implementation of Evidence-Based Programs (Exceptional Children, 2013)

- Active Implementation Frameworks for Successful Service Delivery: Catawba County Child Wellbeing Project (Research on Social Work Practice, 2014)

- The Active Implementation Frameworks: A roadmap for advancing implementation of Comprehensive Medication Management in primary care (Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2017)

In 2009, Veterans Affairs researchers developed a menu of constructs found to be associated with effective implementation across 13 scientific disciplines. Their goal was to review the wide range of terminology and varying definitions used in implementation research, then construct an organizing framework that considered them all. The resulting Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) has been widely cited and has been found useful across a range of disciplines in diverse settings. Designed to guide the systematic assessment of multilevel implementation contexts, the CFIR helps identify factors that might influence the implementation and effectiveness of interventions. The CFIR provides a menu of constructs associated with effective implementation, reflecting the state-of-the-science at the time of its development in 2009. By offering a framework of constructs, the CFIR promotes consistent use, systematic analysis, and organization of findings from implementation studies. In 2022, the CFIR was updated based on feedback from CFIR users, addressing critiques by updating construct names and definitions, adding missing constructs, and dividing existing constructs for needed nuance. A CFIR Outcomes Addendum was also published in 2022, to offer clear conceptual distinctions between types of outcomes for use with the CFIR, helping bring clarity as researchers think about which outcomes are most appropriate for their research question.

For additional resources, please visit the CFIR Technical Assistance Website. The website has tools and templates for studying implementation of innovations using the CFIR framework, and these tools can help you learn more about issues pertaining to inner and outer contexts. You can read the original framework development article in the Open Access (✪) journal Implementation Science.

Learn More:

- ✪ Evaluating and Optimizing the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for use in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review (Implementation Science, 2020)

- ✪ A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Implementation Science, 2017)

- Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: A rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation (Implementation Science, 2017)

- ✪ The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Advancing implementation science through real-world applications, adaptations, and measurement (Implementation Science, 2015)

- 💻 WEBINAR: Use of theory in implementation research: Pragmatic application and scientific advancement of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Dr. Laura Damschroder, National Cancer Institute of NIH Fireside Chat Series)

- 💻 Updated CFIR, Explained (University of Pittsburgh DISC)

The Dynamic Sustainability Framework arose from the need to better understand how the sustainability of health interventions can be improved. In 2013, Chambers, Glasgow, and Stange published ✪ The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change in the Open Access (✪) journal Implementation Science. While traditional models of sustainability often assume diminishing benefits over time, this framework challenges those assumptions. It emphasizes continuous learning, problem-solving, and adaptation of interventions within multi-level contexts. Rather than viewing sustainability as an endgame, the framework encourages ongoing improvement and integration of interventions into local organizational and cultural contexts. By focusing on fit between interventions and their changing context, the Dynamic Sustainability Framework aims to advance the implementation, transportability, and impact of health services research.

Examples of Use

- ✪ Results-based aid with lasting effects: Sustainability in the Salud Mesoamérica Initiative (Globalization and Health, 2018)

- ✪ Study Protocol: A Clinical Trial for Improving Mental Health Screening for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Pregnant Women and Mothers of Young Children Using the Kimberley Mum’s Mood Scale (BMC Public Health, 2019)

- ✪ Sustainability of Public Health Interventions: Where Are the Gaps? (Health Research Policy and Systems, 2019)

In 2008, Feldstein and Glasgow developed the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) to address the lack of consideration of non-research settings in efficacy and effectiveness trials. This model evaluates how the intervention interacts with recipients to influence program adoption, implementation, maintenance, reach, and effectiveness. The framework development article was published by The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. In 2022, Rabin and colleagues published a follow up article, ‘A citation analysis and scoping systematic review of the operationalization of the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM)‘ which aimed to assess the use of the PRISM framework and to make recommendations for future research.

Examples of Use

- Using the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) to Qualitatively Assess Multilevel Contextual Factors to Help Plan, Implement, Evaluate, and Disseminate Health Services Programs (Translational Behavioral Medicine, 2019)

- Stakeholder Perspectives on Implementing a Universal Lynch Syndrome Screening Program: A Qualitative Study of Early Barriers and Facilitators (Genetics Medicine, 2016)

- Evaluating the Implementation of Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) in Five Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Hospitals (The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 2018)

- ✪ Applying an equity lens to assess context and implementation in public health and health services research and practice using the PRISM framework (Frontiers in Health Services, 2023)

- ✪ Integrating the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model With Best Practices in Clinical Decision Support Design: Implementation Science Approach (Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2020)

Using collective experience in research, practice development, and quality improvement efforts, Kitson, Harvey and McCormack proposed in 1998 that success in implementation is a result of the interactions between evidence, context, and facilitation. Their resulting Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework posits that successful implementation requires clear understanding of the evidence in use, the context involved, and the type of facilitation utilized to achieve change.

The original framework development article, Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework is available Open Access (✪) from BMJ Quality & Safety.

Learn More:

- Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework (BMJ Quality & Safety, 2002)

- Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARIHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges (Implementation Science, 2008)

- ✪ A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework (Implementation Science, 2010)

- ✪ A Guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation (Implementation Science, 2011)

- 💻 WEBINAR: Use of theory in implementation research; Pragmatic application and scientific advancement of the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) framework

In 2005, Michie and colleagues published the Theoretical Domains Framework in BMJ Quality & Safety, the result of a consensus process to develop a theoretical framework for implementation research. The primary goals of the development team were to determine key theoretical constructs for studying evidence-based practice implementation and for developing strategies for effective implementation, and for these constructs to be accessible and meaningful across disciplines.

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) is an integrative framework developed to facilitate the investigation of determinants of behavior change and the design of behavior change interventions. Unlike a specific theory, the TDF does not propose testable relationships between elements; instead, it provides a theoretical lens through which to view the cognitive, affective, social, and environmental influences on behavior. Researchers use the TDF to assess implementation problems, design interventions, and understand change processes.

Learn More

- ✪ Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research (Implementation Science, 2012)

- ✪ Theoretical domains framework to assess barriers to change for planning health care quality interventions: a systematic literature review (Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 2016)

- ✪ Combined use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF): a systematic review (Implementation Science, 2017)

- ✪ Applying the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and targeted interventions to enhance nurses’ use of electronic medication management systems in two Australian hospitals (Implementation Science, 2017)

- ✪ A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems (Implementation Science, 2017)

Examples of Use

- ✪ Hospitals Implementing Changes in Law to Protect Children of Ill Parents: A Cross-Sectional Study (BMC Health Services Research, 2018)

- Addressing the Third Delay: Implementing a Novel Obstetric Triage System in Ghana (BMJ Global Health, 2018)

Classic Theories

Used to understand and/or explain what influences implementation outcomes

In 2005 the NIH published ✪ Theory at a Glance: A Guide For Health Promotion Practice 2.0 , an overview of behavior change theories. Below are selected theories from the intrapersonal and interpersonal ecological levels most relevant to implementation science.

Intrapersonal Theories

There are two intrapersonal behavioral theories most often used to interpret individual behavior variation:

The Health Belief Model: An initial theory of health behavior, the HBM arose from work in the 1950s by a group of social psychologists in the U.S. wishing to understand why health improvement services were not being used. The HBM posited that in the health behavior context, readiness to act arises from six factors: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity. perceived benefits, perceived barriers, a cue to action, and self-efficacy. To learn more about the Health Belief Model, please read “Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model” (Health Education Monographs).

The Theory of Planned Behavior: This theory, developed by Ajzen in the late 1980s and formalized in 1991, sees the primary driver of behavior as being behavioral intention. Through the lens of the TPB, behavioral intention is believed to be influenced by an individual’s attitude, their perception of peers’ subjective norms, and the individual’s perceived behavioral control.

Interpersonal Theories

At the interpersonal behavior level, where individual behavior is influenced by a social environment, Social Cognitive Theory is the most widely used theory in health behavior research.

Social Cognitive Theory: Published by Bandera in the 1978 article, Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change, SCT consists of six main constructs: reciprocal determinism, behavioral capability, expectations, observational learning, reinforcements, and self-efficacy (which is seen as the most important personal factor in changing behavior).

Examples of use in implementation science:

The Health Belief Model

- ✪ Using technology for improving population health: comparing classroom vs. online training for peer community health advisors in African American churches (Implementation Science, 2015)

The Theory of Planned Behavior

- ✪ Assessing mental health clinicians’ intentions to adopt evidence-based treatments: reliability and validity testing of the evidence-based treatment intentions scale (Implementation Science, 2016)

Social Cognitive Theory

Diffusion of Innovation Theory is one of the oldest social science theories. It originated in communication to explain how, over time, an idea or product gains momentum and diffuses (or spreads) through a specific population or social system. The theory describes the pattern and speed at which new ideas, practices, or products spread through a population. Diffusion of Innovation theory has its roots in the early twentieth century, but the modern theory is credited to Everett Rogers with his publication in 1962 of Diffusion of Innovations.

This theory holds that adopters of an innovation can be split into five categories that distribute in a Bell curve over time: innovators (2.5%), early adopters (13.5%), early majority (34%), late majority (34%) and laggards (16%). Further, the theory states that any given adopter’s desire and ability to adopt an innovation is individual, based on information about, exposure to, and experience of the innovation and adoption process.

Learn More:

- Diffusion of preventive innovations (Addictive Behaviors, 2002)

- ✪ Diffusion of Innovation Theory (Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 2011)

- Diffusion Of Innovations Theory, Principles, And Practice (Health Affairs, 2018)

- 💻 Making Sense of Diffusion of Innovations Theory (University of Pittsburgh DISC)

- 💻 5 Common Misconceptions about Diffusion of Innovations Theory (University of Pittsburgh DISC)

Organizational theory plays a crucial role in implementation science, offering valuable insights into the complex interactions between organizations and their external environments. In 2017 Dr. Sarah Birken and colleagues published their application of four organizational theories to published accounts of evidence-based program implementation. The objective was to determine whether these theories could help explain implementation success by shedding light on the impact of the external environment on the implementing organizations.

Their paper, ✪ Organizational theory for dissemination and implementation research, published in the journal Implementation Science utilized transaction cost economics theory, institutional theory, contingency theories, and resource dependency theory for this work.

In 2019, Dr. Jennifer Leeman and colleagues applied these same three organizational theories to case studies of the implementation of colorectal cancer screening interventions in Federally Qualified Health Centers, in ✪ Advancing the use of organization theory in implementation science (Preventive Medicine, 2019).

Organizational theory provides a lens through which implementation researchers can better comprehend the intricate relationships between organizations and their surroundings, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness of implementation efforts. Learn more in Leeman et al.’s 2022 article, Applying Theory to Explain the Influence of Factors External to an Organization on the Implementation of an Evidence-Based Intervention, and Birken et al.’s 2023 article, Toward a more comprehensive understanding of organizational influences on implementation: the organization theory for implementation science framework.

Implementation Theories

Used to understand and/or explain what influences implementation outcomes

Implementation climate refers to a shared perception among intended users of an innovation within an organization. It reflects the extent to which an organization’s implementation policies and practices encourage, cultivate, and reward the use of that innovation. In other words, a strong implementation climate indicates that innovation use is expected, supported, and rewarded, leading to more consistent and high-quality implementation within the organization. This construct is particularly relevant for innovations that require coordinated behavior change by multiple organizational members for successful implementation and anticipated benefits. ✪ The meaning and measurement of implementation climate (2011) by Weiner, Belden, Bergmire, and Johnston, posits that the extent to which organizational members perceive that the use of an innovation is expected, supported, and rewarded, is positively associated with implementation effectiveness.

Learn More:

- ✪ A stepped-wedge randomized trial investigating the effect of the Leadership and Organizational Change for Implementation (LOCI) intervention on implementation and transformational leadership, and implementation climate (BMC Health Services Research, 2022)

- ✪ Context matters: measuring implementation climate among individuals and groups (Implementation Science, 2014)

- ✪ Determining the predictors of innovation implementation in healthcare: a quantitative analysis of implementation effectiveness (BMC Health Services Research, 2015)

- ✪ Testing a theory of strategic implementation leadership, implementation climate, and clinicians’ use of evidence-based practice: a 5-year panel analysis (Implementation Science, 2020)

- ✪ Individual-level associations between implementation leadership, climate, and anticipated outcomes: a time-lagged mediation analysis (Implementation Science Communications, 2023)

Normalization Process Theory (NPT) is a sociological theory that helps us understand the dynamics of implementing, embedding, and integrating new technologies or complex interventions in healthcare. It identifies and explains key mechanisms that promote or inhibit the successful implementation of health techniques, technologies, and other interventions. Researchers and practitioners use NPT to rigorously study implementation processes, providing a conceptual vocabulary for analyzing the success or failure of specific projects. Essentially, NPT sheds light on how new practices become routinely embedded in everyday healthcare practice.

In 2010, Elizabeth Murray and colleagues published ✪ Normalization process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions, comprised of four major components: Coherence, Cognitive Participation, Collective Action, and Reflexive Monitoring. The authors argued that using normalization process theory could enable researchers to think through issues of implementation concurrently while designing a complex intervention and its evaluation. They additionally held that normalization process theory could improve trial design by highlighting possible recruitment or data collection issues.

Learn More:

- ✪ Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory (Implementation Science, 2009)

- ✪ Implementation, context and complexity (Implementation Science, 2016)

- ✪ Understanding implementation context and social processes through integrating Normalization Process Theory (NPT) and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Implementation Science Communications, 2022)

- ✪ Combining Realist approaches and Normalization Process Theory to understand implementation: a systematic review (Implementation Science Communications, 2021)

- ✪ Using Normalization Process Theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: a systematic review (Implementation Science, 2018)

- ✪ Improving the normalization of complex interventions: part 1 – development of the NoMAD instrument for assessing implementation work based on normalization process theory (NPT) (BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2018)

- 🎥 Strategic Intentions and Everyday Practices: What do Normalization Processes Look Like?

Organizational Readiness for Change is a multi-level, multi-faceted construct that plays a crucial role in successful implementation of complex changes in healthcare settings. At the organizational level, it refers to two key components: change commitment (organizational members’ shared resolve to implement a change) and change efficacy (their shared belief in their collective capability to carry out the change). This theory suggests that organizational readiness for change varies based on how much members value the change and how favorably they appraise factors like task demands, resource availability, and situational context. When readiness is high, members are more likely to initiate change, persist, and exhibit cooperative behavior, leading to more effective implementation.

In 2009, Bryan Weiner developed a theory of organizational readiness for change to address the lack of theoretical development or empirical study of the commonly used construct. In the Open Access (✪) development article, organizational readiness for change is conceptually defined and a theory of its determinants and outcomes is developed. The focus on the organizational level of analysis filled a theoretical gap necessary to address in order to refine approaches to improving healthcare delivery entailing collective behavior change and in 2014, Shea et al published a measure of organizational readiness for implementing change, based on Weiner’s 2009 theory, available Open Access (✪) in the journal Implementation Science.

Learn More:

- Review: Conceptualization and Measurement of Organizational Readiness for Change (Medical Care Research and Review, 2008)

- ✪ Unpacking organizational readiness for change: an updated systematic review and content analysis of assessments (BMC Health Services Research, 2020)

- ✪ Towards evidence-based palliative care in nursing homes in Sweden: a qualitative study informed by the organizational readiness to change theory (Implementation Science, 2018)

- ✪ Assessing the reliability and validity of the Danish version of Organizational Readiness for Implementing Change (ORIC) (Implementation Science, 2018)

- ✪ Psychometric properties of two implementation measures: Normalization MeAsure Development questionnaire (NoMAD) and organizational readiness for implementing change (ORIC) (Implementation Science Research and Practice, 2024)

Evaluation Frameworks

Used to systematically evaluate implementation success

The FRAME (Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications-Enhanced) is an expanded framework designed to characterize modifications made to evidence-based interventions during implementation. It was developed to address limitations in the original framework (Framework for Modification and Adaptations), which did not fully capture certain aspects of modification and adaptation. The updated FRAME includes the following eight components:

- Timing and Process: Describes when and how the modification occurred during implementation.

- Planned vs. Unplanned: Differentiates between planned/proactive adaptations and unplanned/reactive modifications.

- Decision-Maker: Identifies who determined that the modification should be made.

- Modified Element: Specifies what aspect of the intervention was modified.

- Level of Delivery: Indicates the level (e.g., individual, organization) at which the modification occurred.

- Context or Content-Level Modifications: Describes the type or nature of the modification.

- Fidelity Consistency: Assesses the extent to which the modification aligns with fidelity.

- Reasons for Modification: Includes both the intent/goal of the modification (e.g., cost reduction) and contextual factors that influenced the decision.

The FRAME can be used to support research on the timing, nature, goals, and impact of modifications to evidence-based interventions. Additionally, there is a related tool called FRAME-IS (Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Implementation Strategies), which focuses on documenting modifications to implementation strategies. Both tools aim to enhance our understanding of how adaptations and modifications influence implementation outcomes.

Examples of Use

In their 2011 publication, Proctor and colleagues proposed that implementation outcomes should be distinct from service outcomes or clinical outcomes. They identified eight discrete implementation outcomes and proposed a taxonomy to define them:

- Acceptability: The perception among implementation stakeholders that a given treatment, service, practice, or innovation is agreeable, palatable, or satisfactory

- Adoption: The intention, initial decision, or action to try or employ an innovation or evidence-based practice

- Appropriateness: The perceived fit, relevance, or compatibility of the innovation or evidence-based practice for a given practice setting, provider, or consumer; and/or perceived fit of the innovation to address a particular issue or problem

- Feasibility: The extent to which a new treatment, or an innovation, can be successfully used or carried out within a given agency or setting

- Fidelity: The degree to which an intervention was implemented as it was prescribed in the original protocol or as it was intended by the program developers

- Implementation cost: The cost impact of an implementation effort

- Penetration: The integration of a practice within a service setting and its subsystems

- Sustainability: The extent to which a newly implemented treatment is maintained or institutionalized within a service setting’s ongoing, stable operations

The framework development article, ✪ Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda, is available through Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. In 2023, Dr. Proctor and several colleagues published a follow up Ten years of implementation outcomes research: a scoping review in the journal Implementation Science, a scoping review of ‘the field’s progress in implementation outcomes research.’

Examples of Use

- Toward Evidence-Based Measures of Implementation: Examining the Relationship Between Implementation Outcomes and Client Outcomes (Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 2016)

- ✪ Toward criteria for pragmatic measurement in implementation research and practice: a stakeholder-driven approach using concept mapping (Implementation Science, 2017)

- ✪ German language questionnaires for assessing implementation constructs and outcomes of psychosocial and health-related interventions: a systematic review (Implementation Science, 2018)

- The Elusive Search for Success: Defining and Measuring Implementation Outcomes in a Real-World Hospital Trial (Frontiers In Public Health, 2019)

The RE-AIM framework helps program planners, evaluators, and researchers consider five dimensions when designing, implementing, and assessing interventions:

- Reach: The extent to which an intervention reaches the intended target population, considering both the absolute number of participants and the representativeness of those participants

- Effectiveness: The impact of the intervention on relevant outcomes, assessing whether the intervention achieves its intended goals and produces positive results

- Adoption: The willingness of organizations or individuals to implement the intervention, considering factors such as organizational buy-in, acceptance, and readiness for change

- Implementation: How well the intervention is delivered in practice, looking at fidelity (adherence to the intervention components), quality, and consistency of delivery

- Maintenance: The long-term sustainability of the intervention, considering whether the program continues to be effective and is integrated into routine practice over time

In 1999, authors Glasgow, Vogt, and Boles developed this framework because they felt tightly controlled efficacy studies weren’t very helpful in informing program scale-up or in understanding actual public health impact of an intervention. The RE-AIM framework has been refined over time to guide the design and evaluation of complex interventions in order to maximize real-life public health impact.

This framework helps researchers collect information needed to translate research to effective practice, and may also be used to guide implementation and potential scale-up activities. You can read the original framework development article in The American Journal of Public Health. Additional resources, support, and publications on the RE-AIM framework can be found at RE-AIM.org. The 2021 special issue of Frontiers in Public Health titled Use of the RE-AIM Framework: Translating Research to Practice with Novel Applications and Emerging Directions includes more than 20 articles on RE-AIM.

Learn More:

- What Does It Mean to “Employ” the RE-AIM Model? (Evaluation & the Health Professions, 2012)

- The RE-AIM Framework: A Systematic Review of Use Over Time (The American Journal of Public Health, 2013)

- ✪ Fidelity to and comparative results across behavioral interventions evaluated through the RE-AIM framework: a systematic review (Systematic Reviews, 2015)

- ✪ Qualitative approaches to use of the RE-AIM framework: rationale and methods (BMC Health Services Research, 2018)

- ✪ RE-AIM in Clinical, Community, and Corporate Settings: Perspectives, Strategies, and Recommendations to Enhance Public Health Impact (Frontiers in Public Health, 2018)

- ✪ RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review (Frontiers in Public Health, 2019)

- ✪ RE-AIM in the Real World: Use of the RE-AIM Framework for Program Planning and Evaluation in Clinical and Community Settings (Frontiers in Public Health, 2019)

- 💻 How to use RE-AIM (University of Pittsburgh DISC)

Saldana’s Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC) is an eight-stage tool that assesses the implementation process and milestones across three phases: pre-implementation, implementation, and sustainability. It helps measure the duration (time to complete a stage), proportion (of stage activities completed), and overall progress of a site in the implementation process. The SIC aims to bridge the gap between the implementation process and associated costs. The eight stages of the SIC are:

- Engagement: Initial involvement and commitment to implementing the practice

- Consideration of Feasibility: Assessing whether the practice can be feasibly implemented

- Readiness Planning: Preparing for implementation by addressing organizational readiness

- Staff Hired and Trained: Recruiting and training staff for implementation

- Fidelity Monitoring Processes in Place: Establishing processes to monitor fidelity to the practice

- Services and Consultation Begin: Actual implementation of the practice

- Ongoing Services and Fidelity Monitoring: Continuation of services and fidelity monitoring

- Competency: Ensuring staff competence in delivering the practice

Learn More:

- ✪ The stages of implementation completion for evidence-based practice: Protocol for a mixed methods study. (Implementation Science, 2014)

- ✪ Agency leaders’ assessments of feasibility and desirability of implementation of evidence-based practices in youth-serving organizations using the Stages of Implementation Completion (Frontiers in Public Health, 2018)

- ✪ Economic evaluation in implementation science: Making the business case for implementation strategies (Psychiatry Research, 2020)

- Scaling Implementation of Collaborative Care for Depression: Adaptation of the Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC) (Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 2020)

- Adapting the stages of implementation completion to an evidence-based implementation strategy: The development of the NIATx stages of implementation completion (Implementation Research and Practice, 2023)

PAUSE AND REFLECT

Does the T/M/F:

❯ specify the social, cultural, economic, and political contexts of the research?

❯ account for the needs and contexts of various demographic groups impacted, particularly those who are historically or currently marginalized or underserved?

❯ recognize and aim to dismantle existing power structures that contribute to inequities, including consideration of who has decision-making power and how it can be equitably distributed?

❯ emphasize building trusting relationships with communities and incorporating community-defined evidence so efforts are culturally relevant?

❯ address macro-, meso-, and micro-level influences on equity?

❯ encourage ongoing critical reflection on how well it advances equity and continue to identify areas for improvement?